预告片 Trailer

|

|

展览前言:

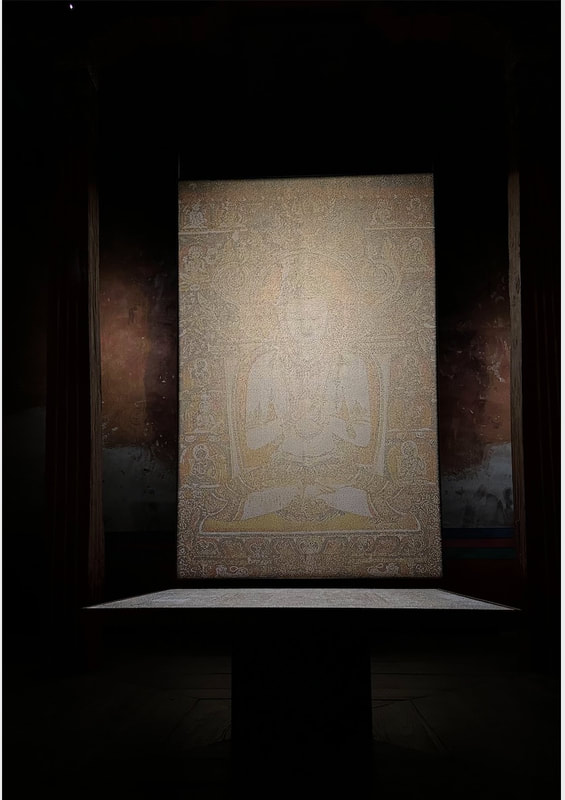

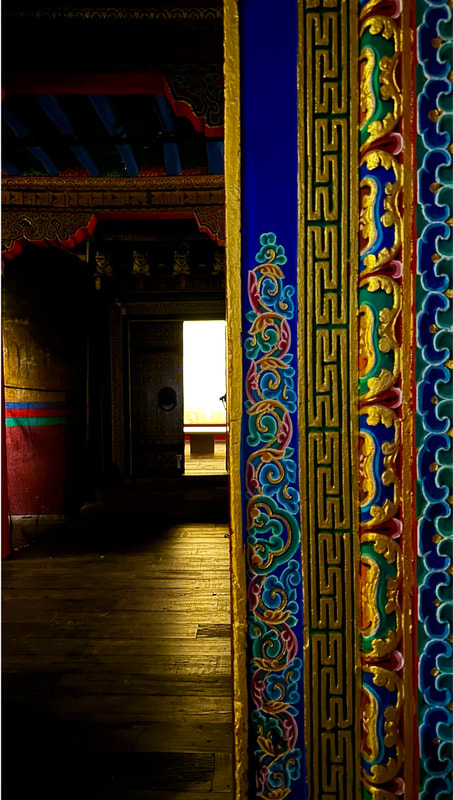

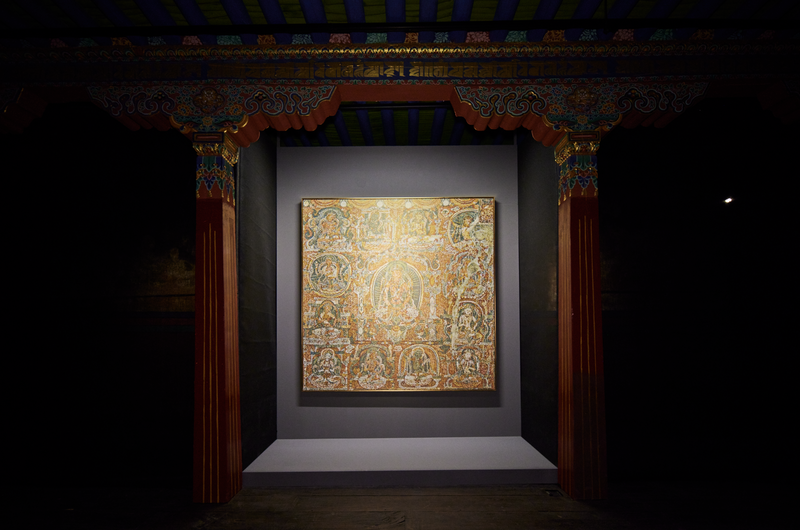

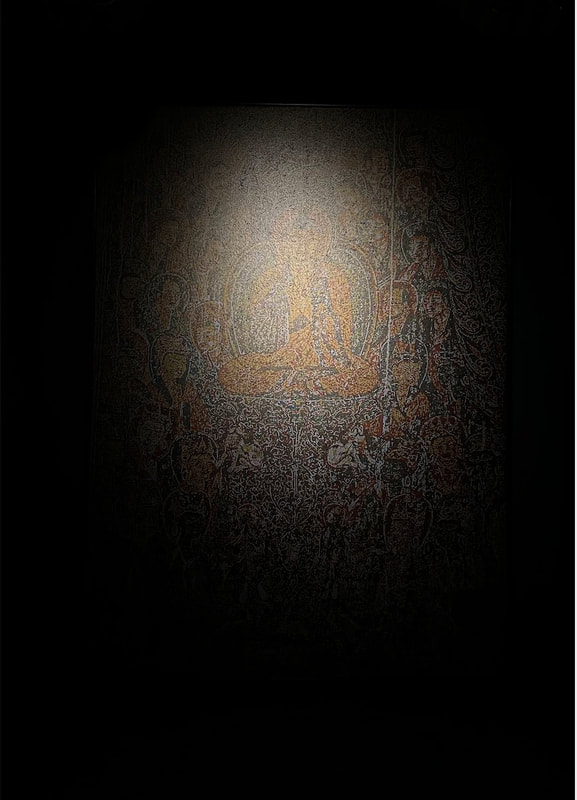

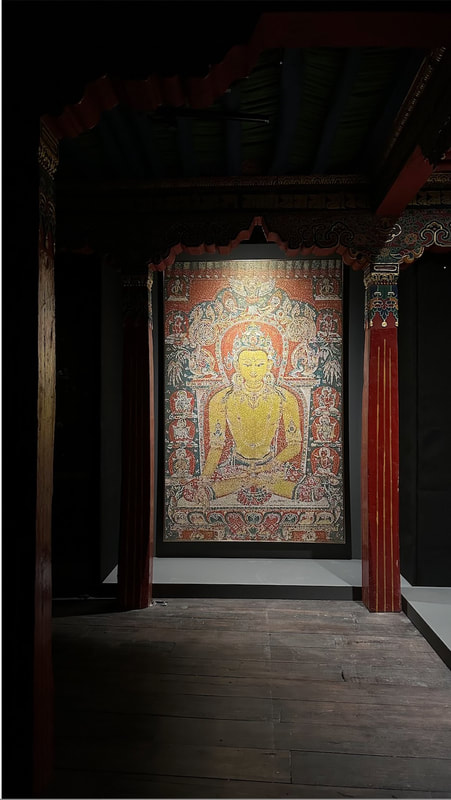

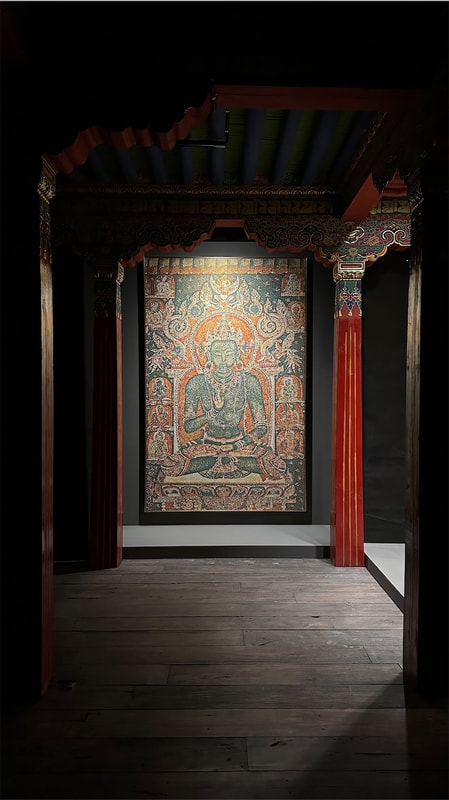

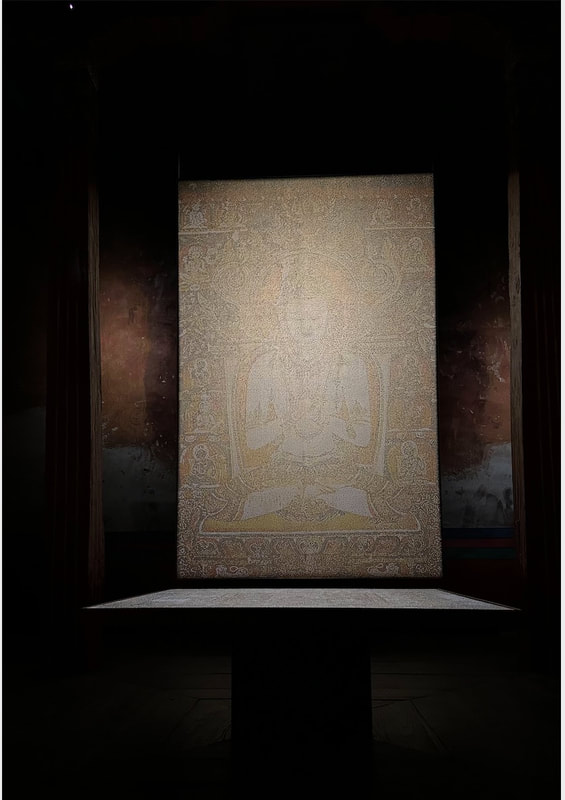

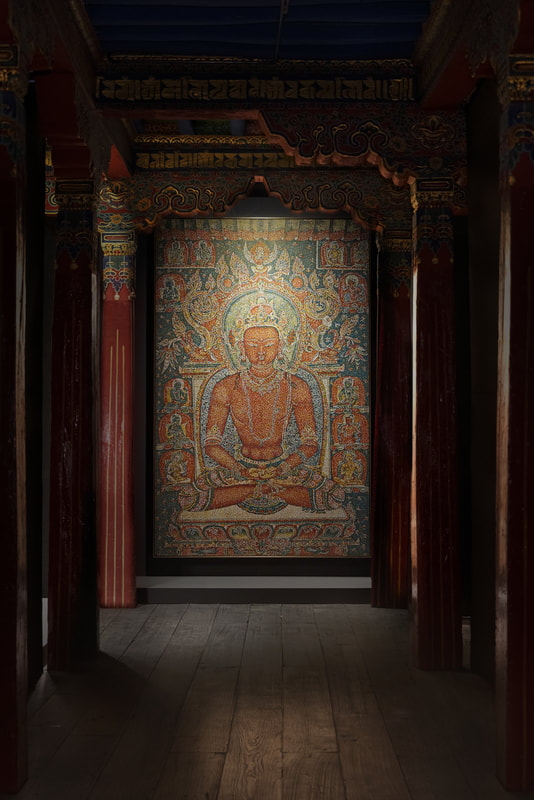

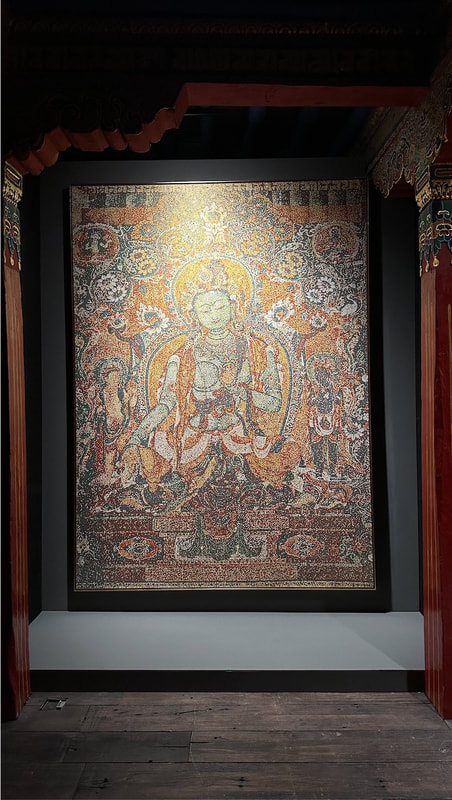

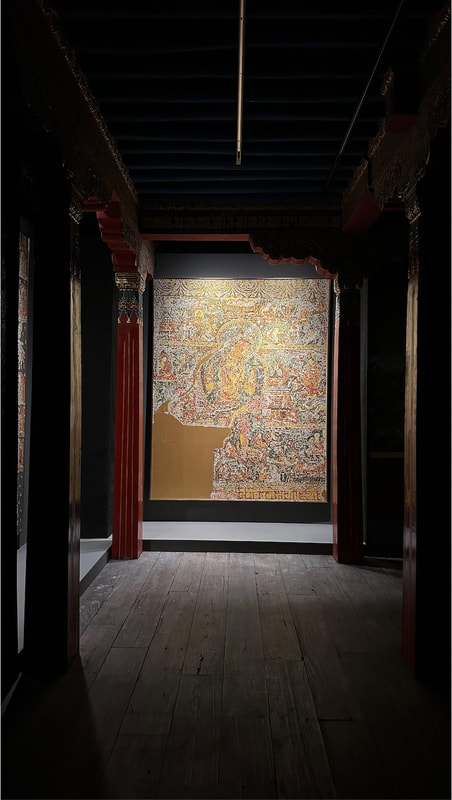

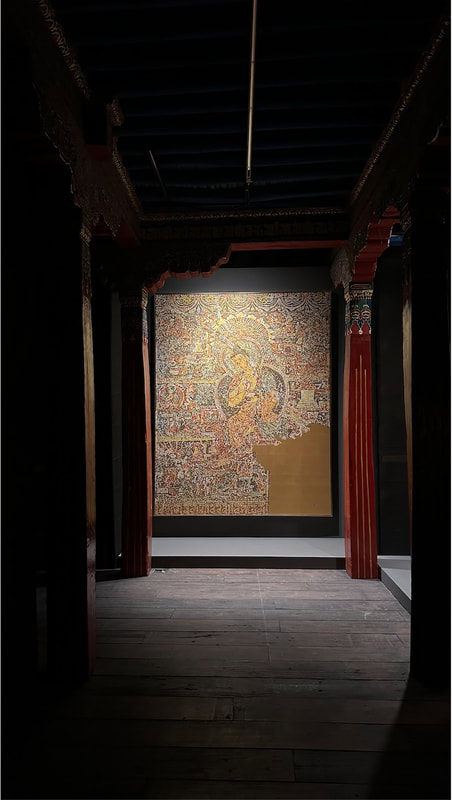

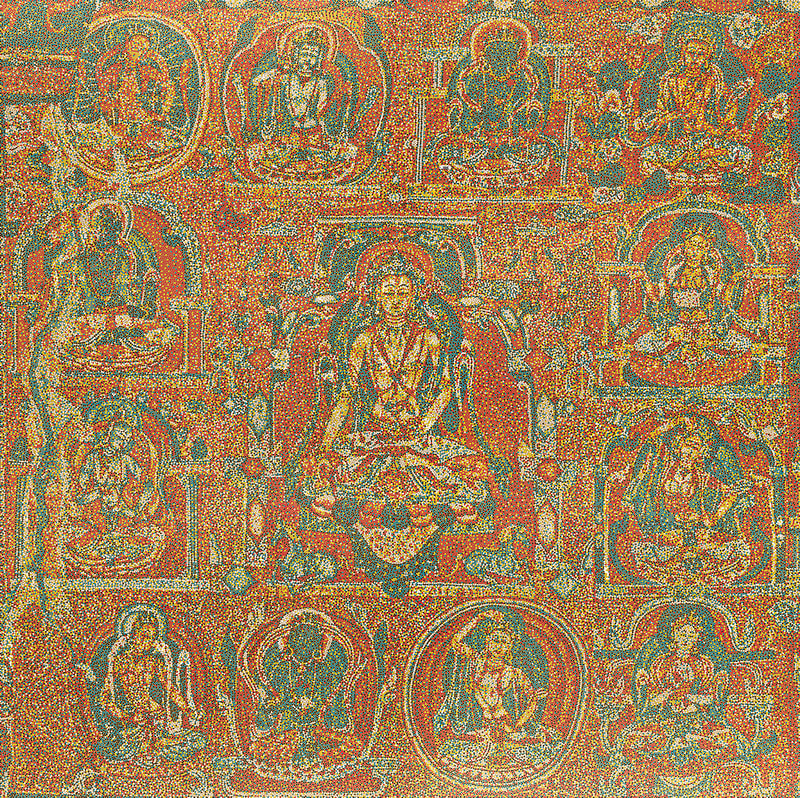

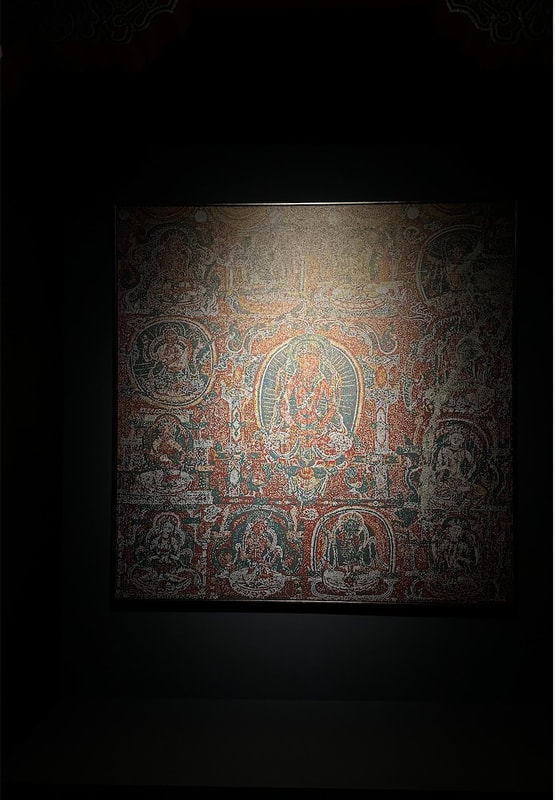

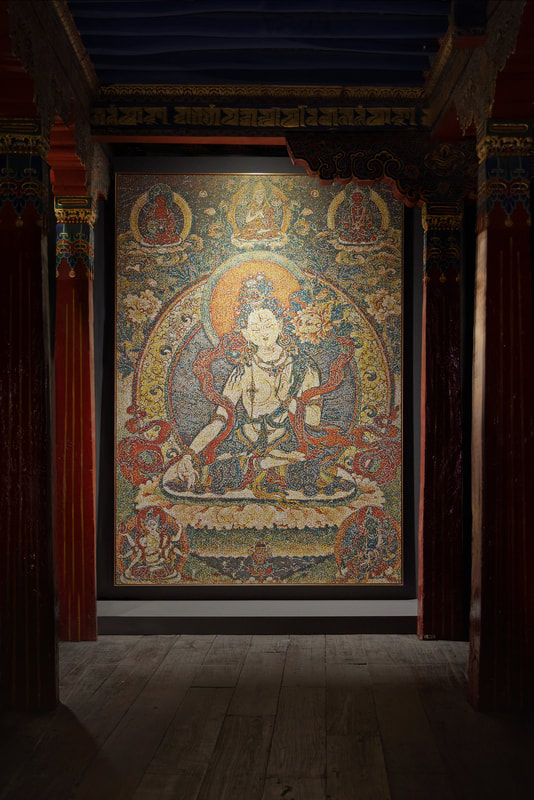

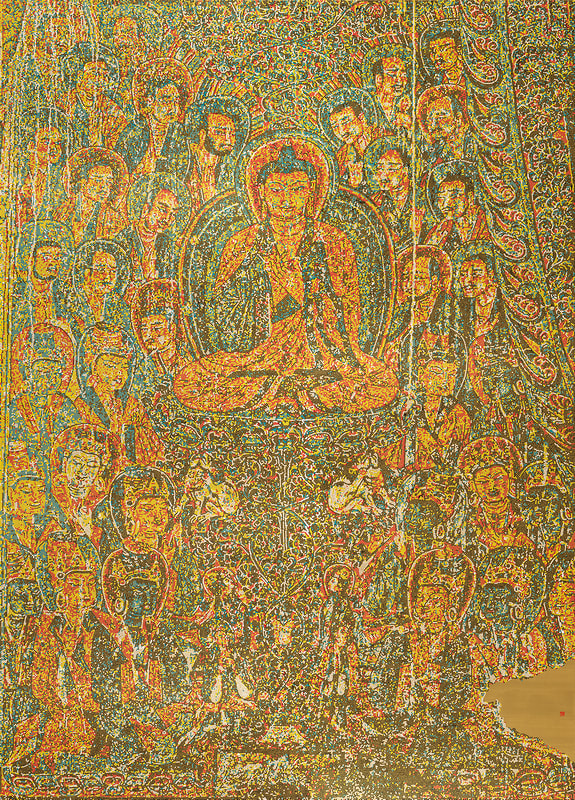

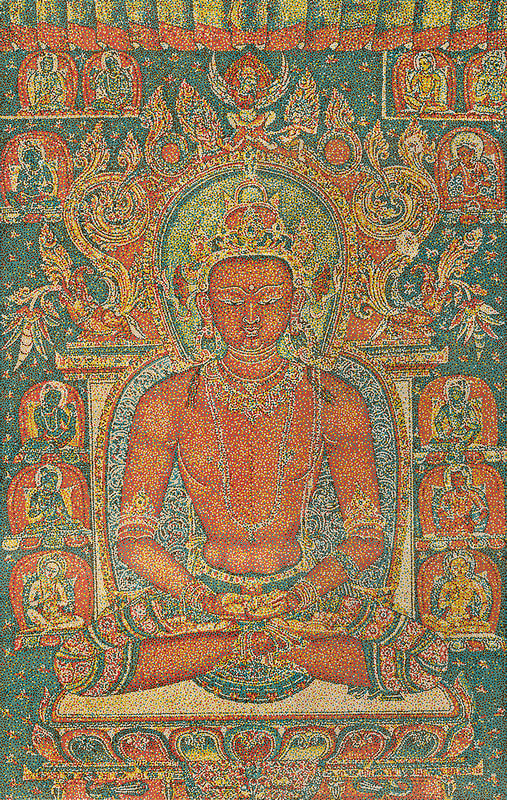

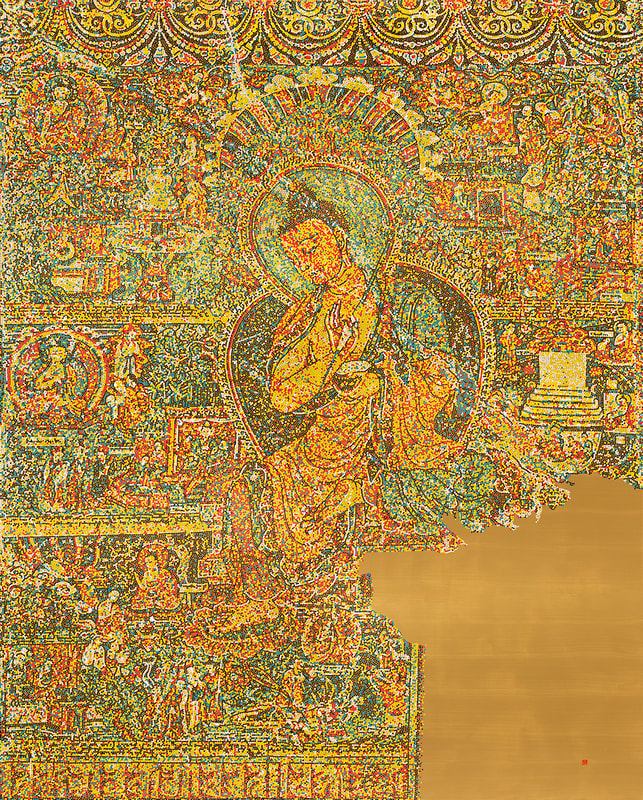

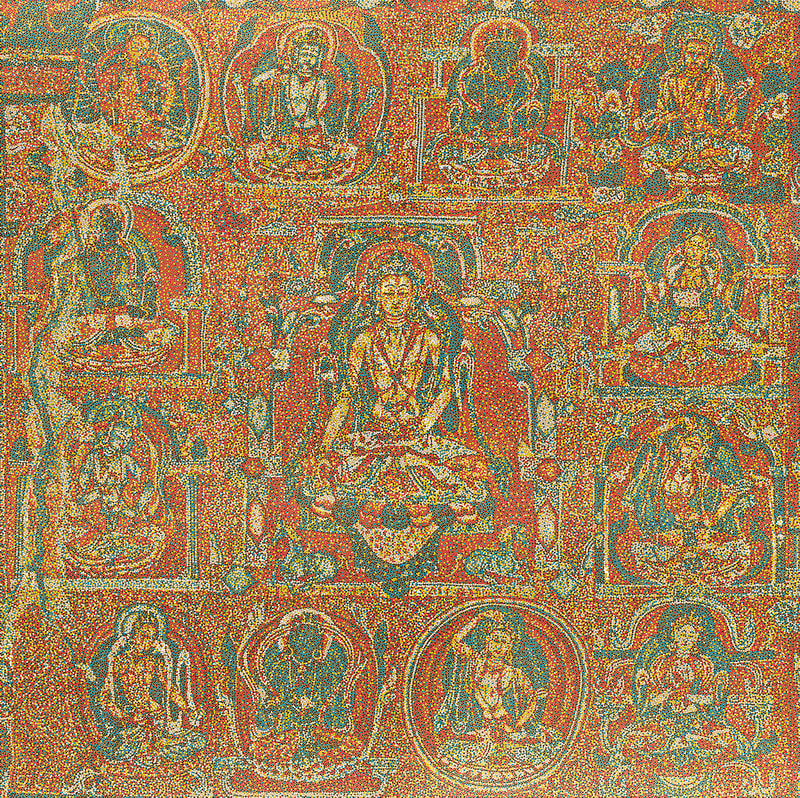

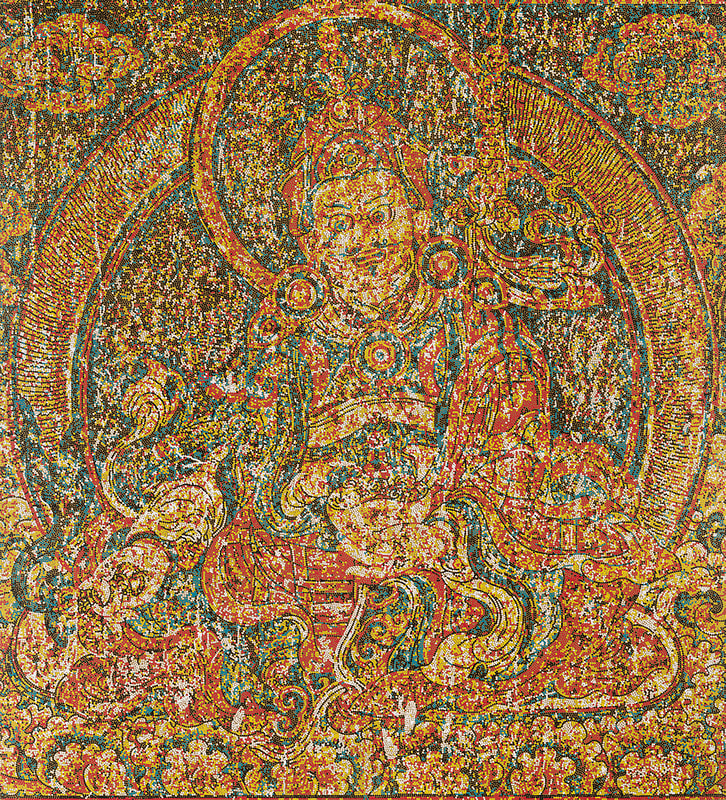

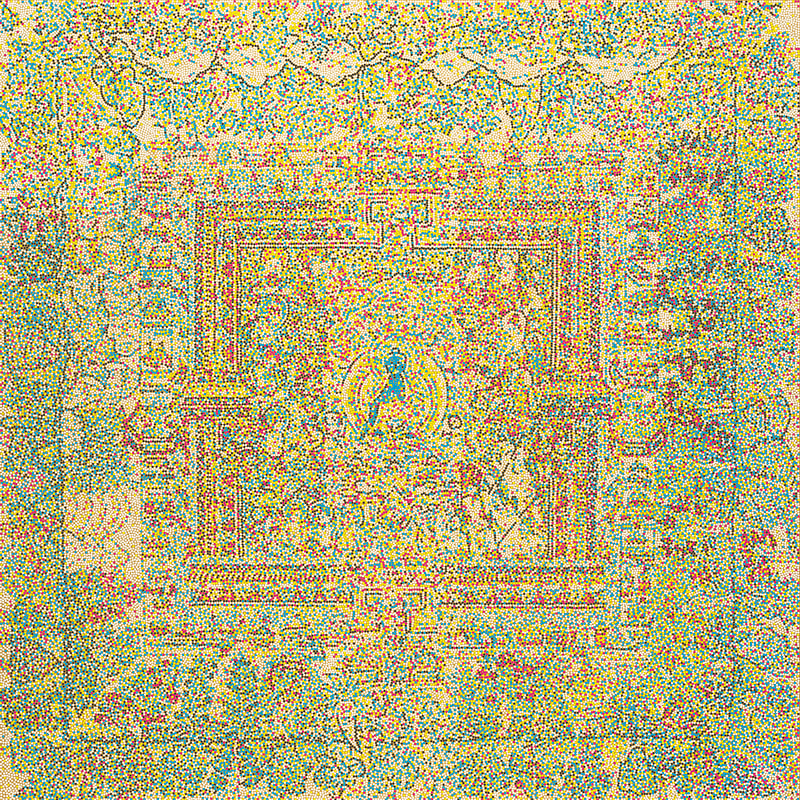

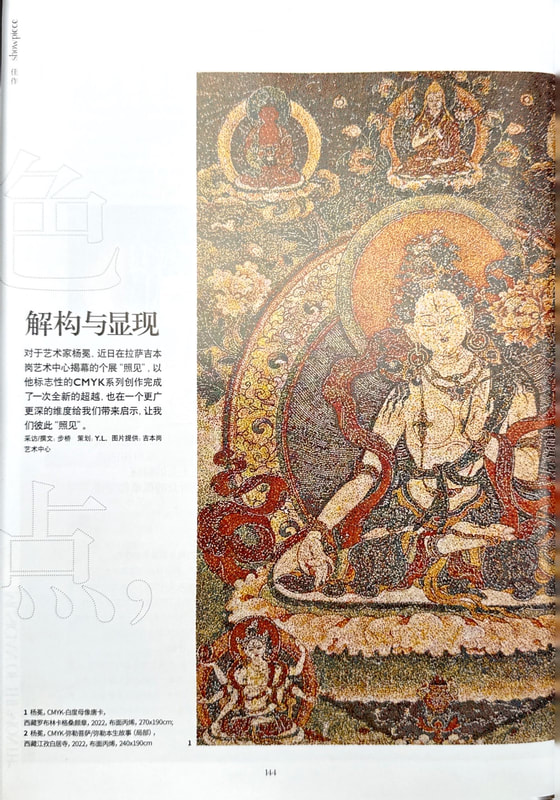

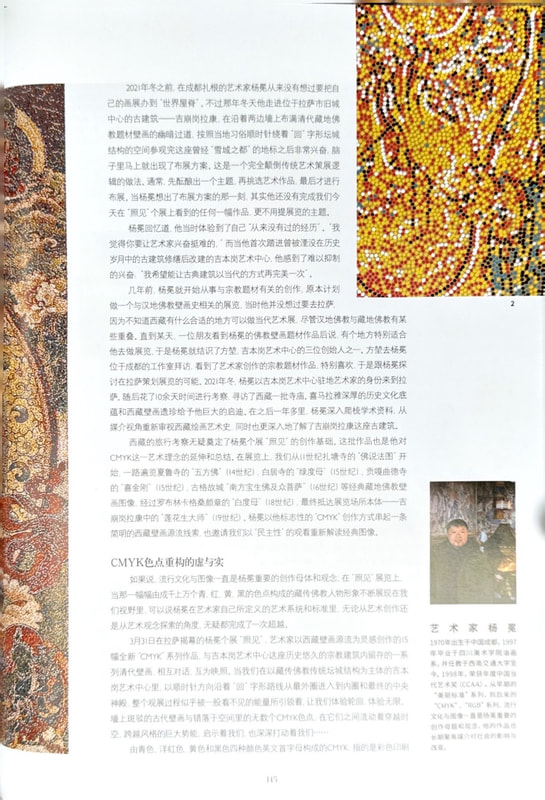

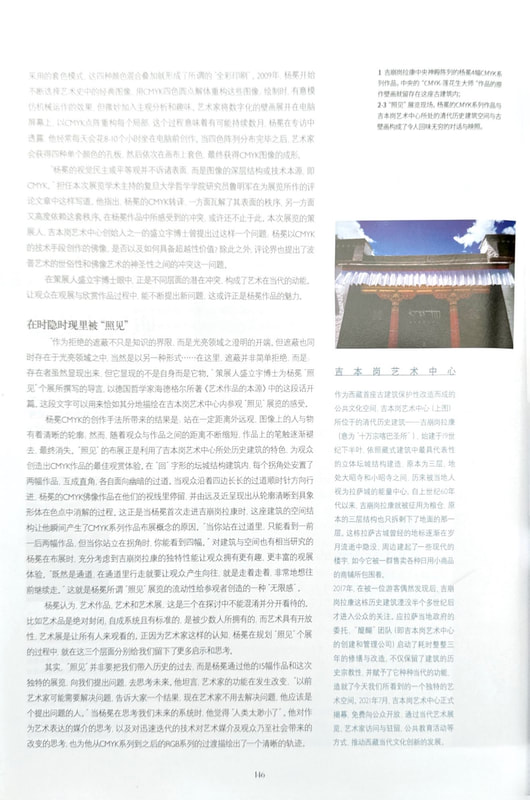

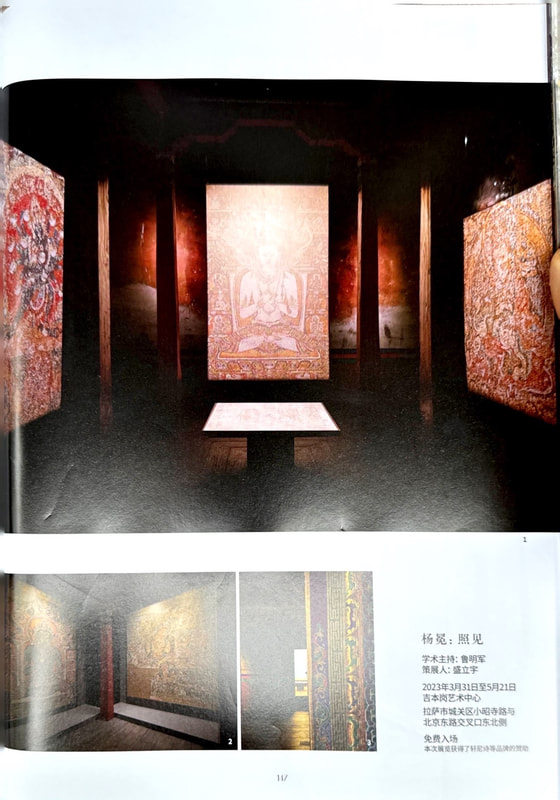

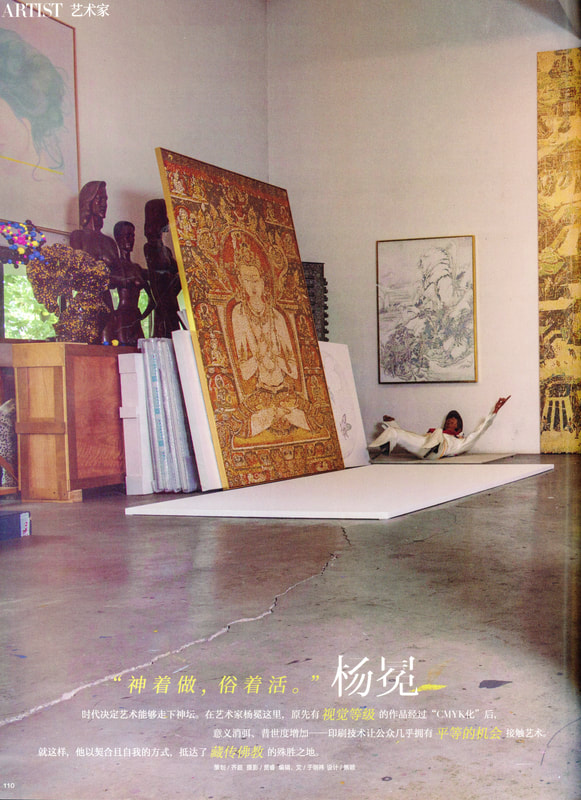

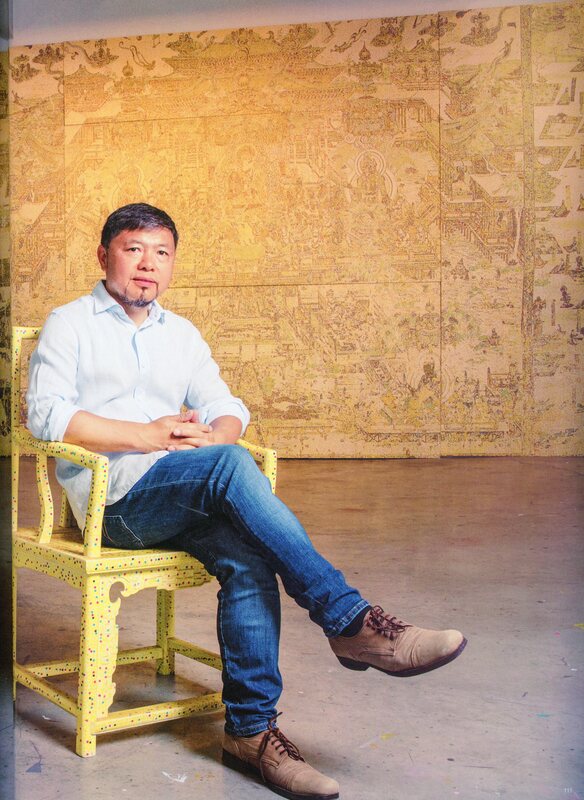

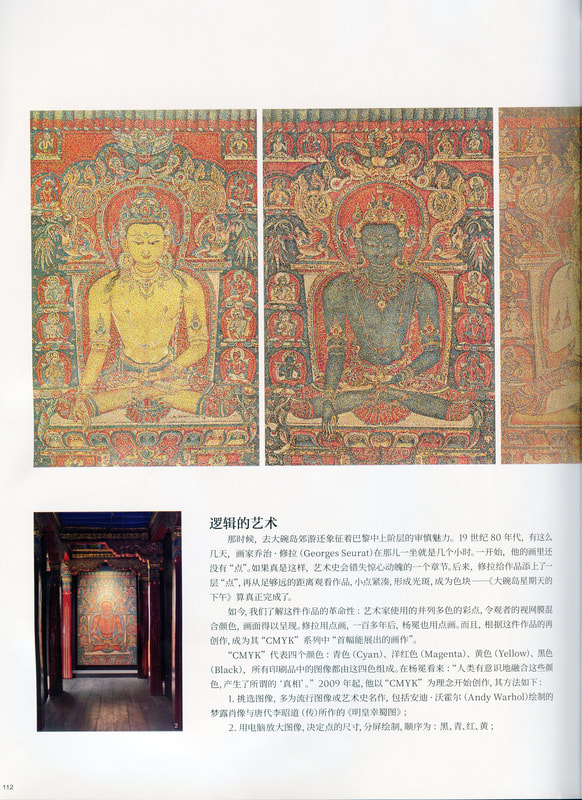

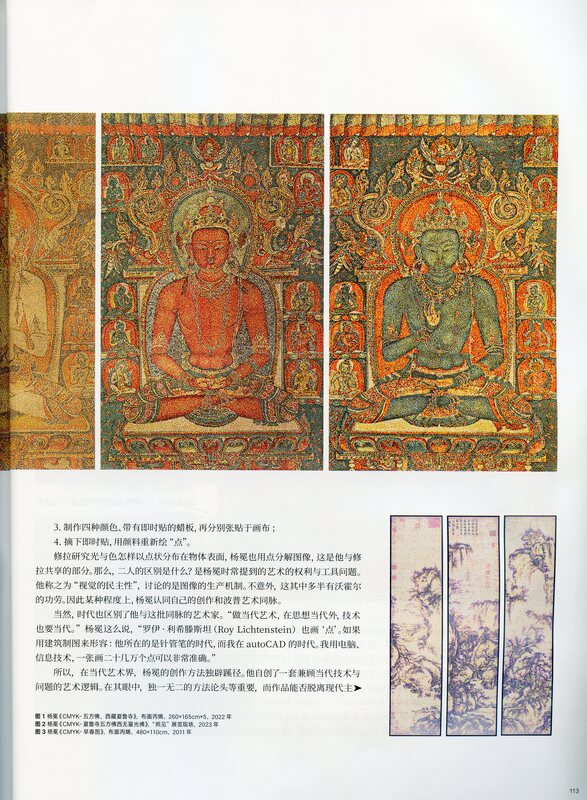

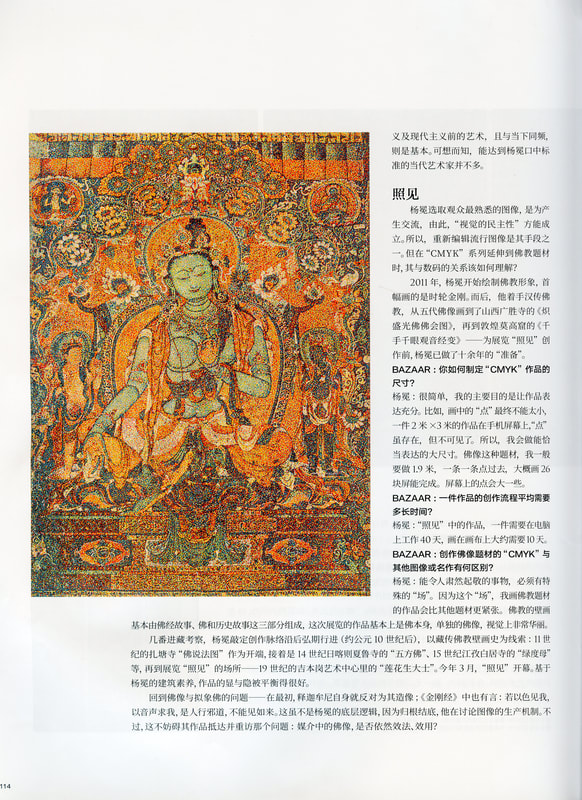

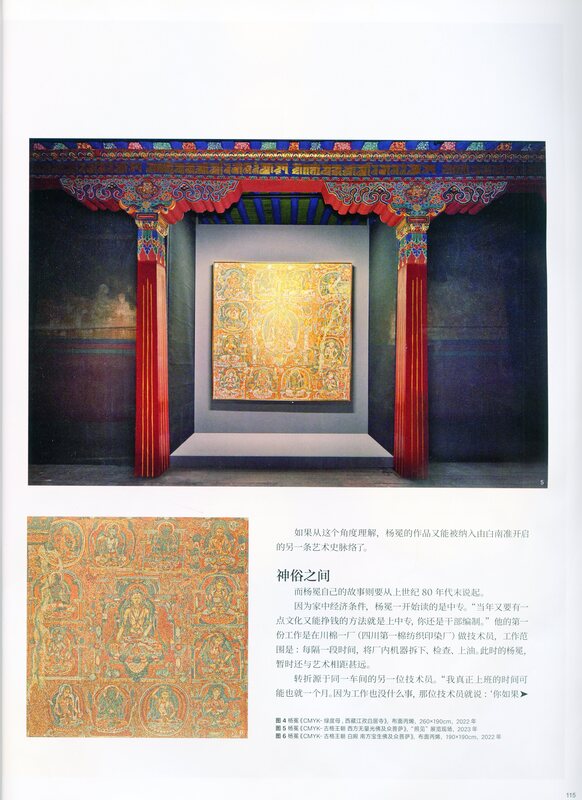

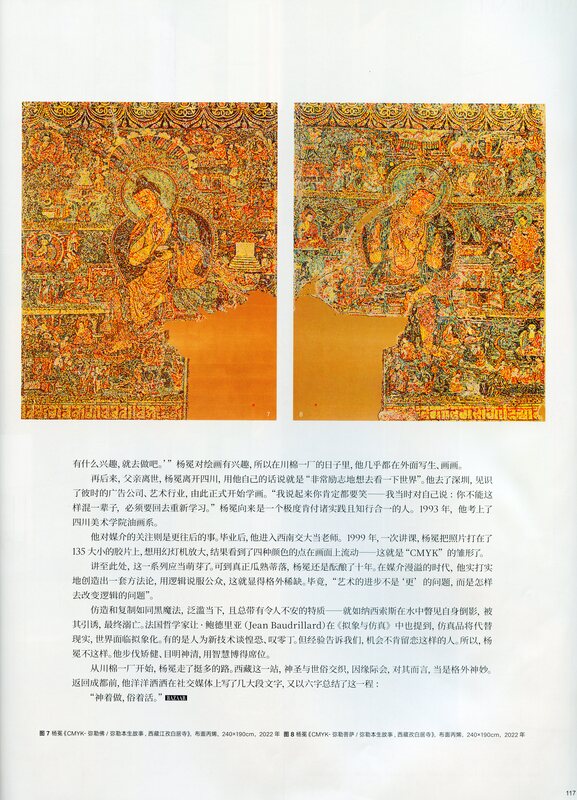

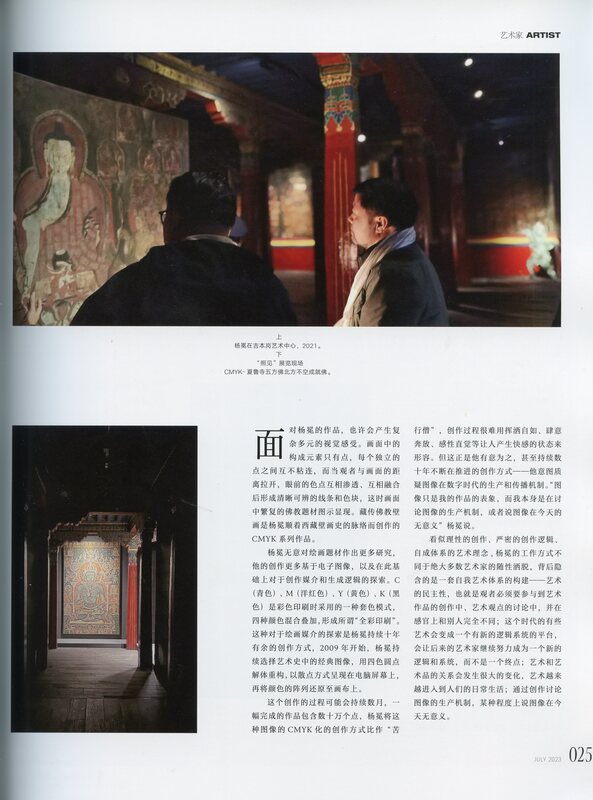

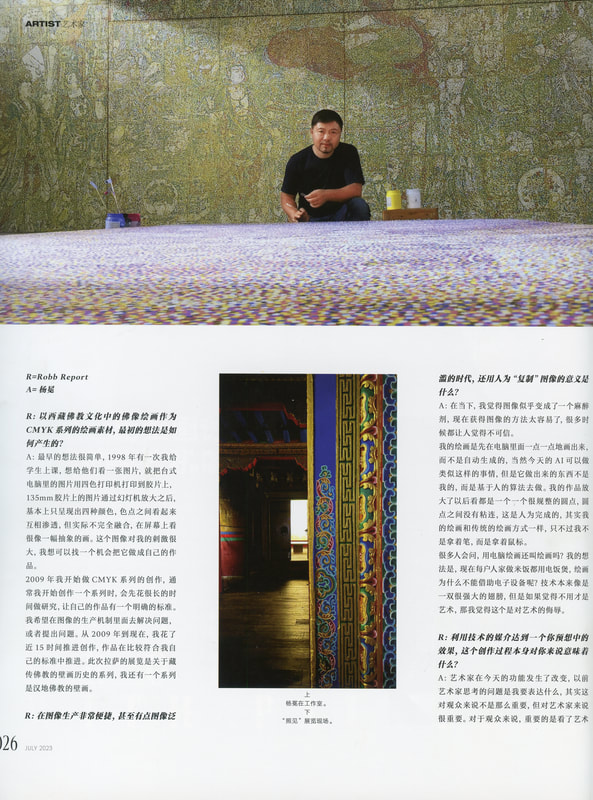

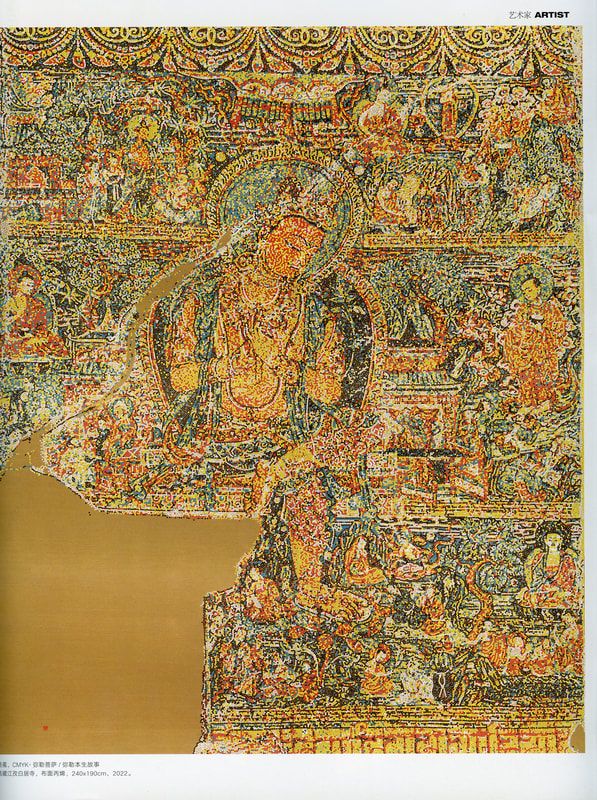

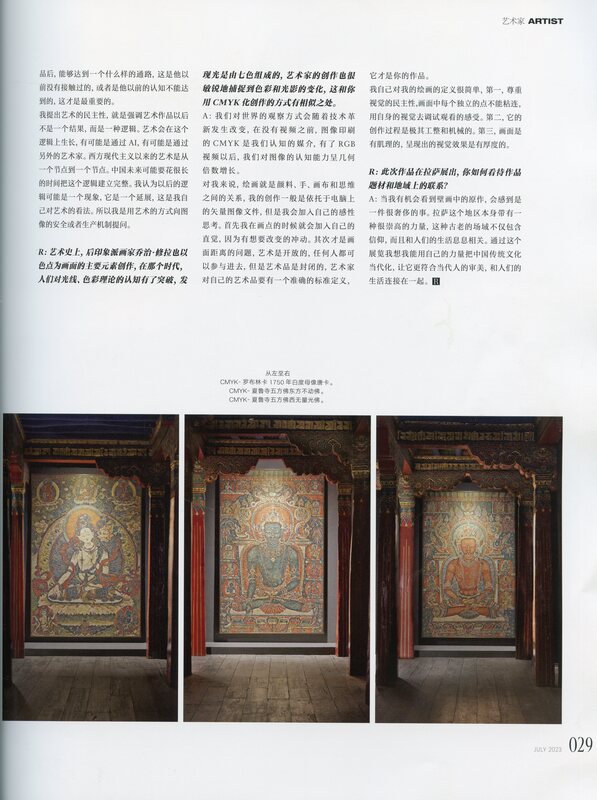

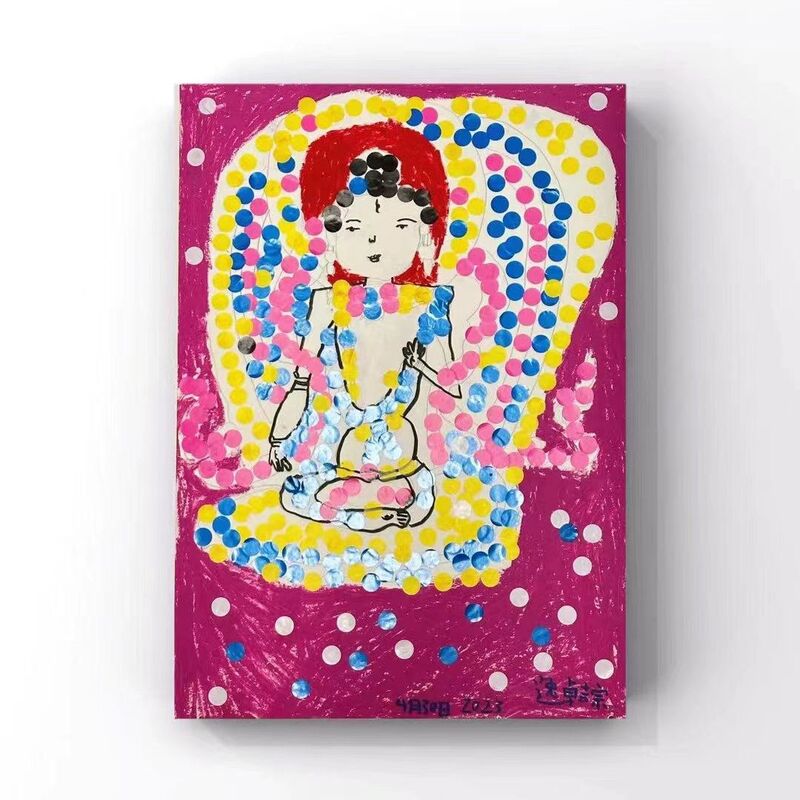

显现和照见 策展人:盛立宇 “作为拒绝的遮蔽不只是知识的一向的界限,而是光亮领域之澄明的开端。但遮蔽也同时存在于光亮领域之中,当然是以另一种方式。存在者蜂拥而动,彼此遮盖,互相掩饰,少量阻隔大量,个别掩盖全体。在这里,遮蔽并非简单拒绝,而是:存在者虽然显现出来,但它显现的不是自身而是它物。”——海德格尔,《艺术作品的本源》,1937 杨冕的工作方式,在以西藏壁画为对象时,产生了技术哲学上的紧张关系。他将数字化的壁画展开在电脑屏幕上,每个局部以CMYK点阵重构,这个工作过程有可能会持续数月。无论是金刚怒目,还是菩萨低眉,都弥散在无数个由青色、洋红色、黑色、黄色构成的色点海洋中。在通过经验和直觉把颜色的阵列分布完毕之后,艺术家会获得四种单个颜色的孔板,依次在画布上套色,图像的“CMYK化”就形成了。 其结果是:从一定距离远观,无论是夏鲁寺的五方佛,还是贡嘎曲德寺的喜金刚,佛像依旧庄严;但如果近距离观看,笔触消失了,杨冕的创作方式看起来匀质、平滑,具有媒体工业属性,观者会发现自己在看完全另外一件事物。 传统上,一幅唐卡是否具有超越性的价值,很大程度上来自画师为之注入的生命力,包含体力的投入和精神的专注。许多画家用唾液湿润笔尖,甚至长时间的作画形成眼疾,都是画家为诸佛菩萨的身体供养。笔触和细节也留下了画家生命注入的痕迹。一张严肃的唐卡作品经常需要数月,有些画家甚至耗费数年。理论上,画面的经营和细节的雕琢可以无止境地进行下去,在绘画的“开脸”、“开眼”阶段,这一过程达到精神性的巅峰,也是佛像完成的最后一步,不亚于一次信仰的仪式。 那问题是:杨冕以上述技术手段创作的佛像,是否以及如何具备超越性价值? 这种潜在的冲突,正是艺术在当代的动能。在现代主义之前,艺术的主要职能是“模拟”(mimesis)。对于西藏的佛像绘画而言,这一模拟有两层含义,其一是对过往经典的临摹,这在其他美术传统亦常见;其二,是试图接近一个佛像的“理想范式”——见即圆满,神圣降临。除了“三十二相”和“八十种好”之外,西藏的佛像绘画以“三经一疏”[1]为蓝本,方便制度化及规范的创作,并为“理想范式”提供信仰层面的依据。 然而时代已变:酥油灯火虽然长明,但占据人们心智更多的是电子屏幕闪烁,人工智能都开始作画;佛像依旧神圣,但拉萨八廓街已随处可见唐卡的印刷品,画面精度与手绘作品难分区别。这种场景下,本雅明百年前对于“灵光”的发问依旧适用,而艺术家需要回应的问题是:数字复制时代的佛像为何? 换一个问题是:属于这个时代的佛像,如何生产,存在于哪里?显然,对任何观者的视网膜而言,作品只是一个四色点阵的集合。杨冕无情地将图像做了一次视觉生产上不亚于原子层面的解构。这也是CMYK系列的底层逻辑:印刷中的大千世界和滚滚红尘,根本上的四种颜色的叠加。现在,艺术家把这四种颜色彻底、直观地拿到面前——告诉你,这就是视觉的真相。数百年来,以身体供养、细豪赋形的佛像创作方式,也变成电子屏幕前鼠标的数百万次点击,并让佛像本质上存在于数据中。这是图像的一次湮灭,但也是一次数字世界的重生,两者或许一体两面,并且切中我们这个时代对网络、数据、虚拟与现实的讨论。 如同历史,凑得越近越看不清,真相需要一定的距离才会显现。当我们退距观看杨冕的佛像时,诸佛菩萨依旧直观地降临了:夏鲁寺五方佛,贡嘎曲德寺的喜金刚,吉本岗艺术中心的威武莲师,在原子化的CMYK色点中依旧向我们呈现佛土庄严。 这是佛像的“显现”。不是逻辑和视觉推理的结果。借用现象学的观点,或许可以说,是因为我们或许对这些图像具有“本质直观”的能力。事物本身和其“显像”,就是所谓“存在论差异”。在这个案例中,CMYK点阵作为“显像”,引领我们通达佛像本身。 这在一定程度上回答了之前的问题,运用这个时代的视觉语法,佛像的真相,可以保存于印刷、屏幕,以及数据中。 杨冕的工作让我们思考媒介对人理解世界的影响。除了印刷术、消费主义、媒介工业化等已被评论家讨论过的议题,这次展览或许呈现了一次特殊的链接:数据与神圣。杨冕的CMYK均匀分布、无穷无尽,有一种对时间和空间匀质性的一种暗合:有对于时间匀质的共识,整个世界才能作为一架巨机器精确地运转;有对空间匀质的共识,北美的物理学家才能认同一个北京实验室的科研成果。这种匀质和原子化,是艺术家对我们这个时代特征的回应。当这些点阵达到“无边无际”之时,或许就会“不可思议”,在局部的混沌中,超越逻辑,向我们敞开这个世界部分的真理。 是为“照见”。 【1】“三经一疏”,即《佛说十拃量度经》(一译《佛像如尼拘落陀树纵广相称十拃量度经》或《舍利弗请问经》)、《佛说造像量度经》(一译《身影像量相》)、《绘画量度经》(一译《画相》或《梵天定书》)和《佛说造像量度经疏》(一译《正觉佛所说身影像量释》)。 An Appearance and an Encounter Sheng Liyu Concealment as a refusal is not simply and only the limit of knowledge in any given circumstance, but the beginning of the lighting of what is lighted. But concealment, though of another sort, to be sure, at the same time also occurs within what is lighted. One being places itself in front of another being, the one helps to hide the other, the former obscures the latter, a few obstruct many, one denies all. Here concealment is not simple refusal. Rather a being appears, but it presents itself as other than it is.[1] -Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art” Yang Mian’s working methods, when focused on Tibetan mural painting, engender a tense relationship with the philosophy of technology. He develops digital murals on a computer screen, and every part is reconstructed in a CMYK matrix, which might take several months. Both the fierce and gentle faces are diffused in a sea of countless cyan, magenta, black, and yellow dots. After arranging the colors based on experience and intuition, Yang creates four boards with holes corresponding to each of the colors, then applies the colors to the canvas one after another and transforms the image into CMYK. If you look at the paintings from a distance, the Buddha images in Five Tathāgatas at the Shalu Monastery and the Hevajra Tantra and Dakini at the Choide Monastery are still solemn and dignified, but if you examine them at close range, the brushstrokes disappear. Yang’s paintings seem even and smooth—a part of the media industry—and viewers discover that they are looking at something else entirely. Traditionally, whether a thangka had transcendental value was largely dependent on the vitality injected by the painter—the investment of physical and spiritual energy. Many painters moisten the tips of their brushes with their saliva and develop eye strain after years of painting, which are physical offerings to the Buddha and bodhisattvas. The brushstrokes and details are imbued with the artist’s vitality. A serious thangka work often requires several months to complete, and some painters spend years. In theory, painters could endlessly adjust the composition and polish the details, achieving a spiritual peak as they complete the final steps in the painting—the “opening” of the faces and eyes—much like a religious ceremony. Now, the question becomes: How could the Buddha images that Yang Mian has made using this technique have transcendental value, if they have any at all? This potential conflict is what gives art energy in the contemporary moment. Prior to modernism, the primary task of art was mimesis. In Tibetan Buddhist painting, there are two facets to mimesis. The first is the imitation of past classic paintings, which is common in other artistic traditions. The second is the attempt to approach an ideal image of the Buddha—when gazing upon this perfection, the sacred comes to earth. In addition to the Thirty-Two Characteristics and the Eighty Secondary Characteristics of a Great Man, Tibetan Buddhist painting uses the Three Sutras and One Commentary[2] as a blueprint, facilitating systematized and standardized painting and offering a foundation in faith for that ideal image. However, the times have already changed. Even though the butter lamps remain lit, glittering screens take up more space in people’s minds and artificial intelligence has started to make art. Images of the Buddha are still holy, but thangka prints are ubiquitous on Barkhor Street, a key commercial street in Lhasa. Their precision makes it difficult to differentiate them from hand-painted works. In this circumstance, Walter Benjamin’s century-old interrogation of the aura of a work of art still applies. Yang must engage with the question: Why make Buddha images in an era of digital replication? In other words, how is a Buddha image for our times produced, and where does it exist? Obviously, for any viewer’s retina, the works are a synthesis of a four-color dot matrix. Yang Mian’s cold approach to the visual production of images is akin to deconstruction on the atomic level. This also encapsulates the underlying logic of CMYK: In printed images, the boundless universe and the mortal world are essentially layers of those four colors. Now, Yang has fully and directly placed these four colors before you—telling you that this is the visual truth. Finely detailed Buddha images that, for several hundred years, were physical offerings have become millions of clicks of a mouse on a computer screen, such that the Buddha images fundamentally exists digitally. This is the destruction of an image, but it is also a rebirth in the digital world; they may be two sides of the same coin that engage with our current discussion of the internet, data, virtuality, and reality. As in history, the closer you get, the less you see; the truth requires a bit of distance before it appears. When we take a few steps back to view Yang Mian’s Buddha images, the Buddha and bodhisattvas are still descending to earth: Five Tathāgatas at the Shalu Monastery, Hevajra Tantra and Dakini at the Choide Monastery, and Padmasambhava at the Jebumgang Art Center. The atomic dots of CMYK color still present to us the dignity of the Buddha. This is the appearance of a Buddha image, rather than the result of logical and visual inferences. Drawing on phenomenology, we may be able to say that this is because we have the ability to perceive these images fundamentally and directly. The thing and its visualization manifest an ontological difference. In this case, the CMYK dot matrix as a visualization leads us toward the Buddha. To a certain extent, this answers the question I posed earlier. Yang uses the visual grammar of our times to preserve the truth of the Buddha’s image in prints, on screens, and in data. Yang Mian’s work inspires us to contemplate the media’s influence on our understanding of the world. In addition to printing technologies, consumerism, the industrialization of media, and other issues that critics have addressed previously, this exhibition may present a special connection between data and the sacred. Yang Mian’s inexhaustible, even distribution of CMYK dots reflect the homogeneity of time and space. Only with a common understanding of time can the entire world operate as a precise machine, and only with a common understanding of space can North American physicists verify research results from a Beijing laboratory. This evenness and atomization are Yang’s response to the characteristics of our times. We may not believe it when these dot matrices become limitless; localized chaos transcends logic, opening for us some of the truths in this world as encounters. References Heidegger, Martin. “The Origin of the Work of Art.” In Basic Writings, edited by David Farrell Krell, 143-187. New York: Harper & Row, 1977. 【1】Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 175-176. 【2】 The Three Sutras and One Commentary are Buddha’s Manual of Ten-Span Dimensions (Foshuo shizha liangdu jing), Buddha’s Manual of Sculptural Dimensions (Foshuo zaoxiang liangdu jing), Painting Pictures (Huaxiang), and Commentary on the Buddha’s Manual of Sculptural Dimensions (Foshuo zaoxiang liangdu jingshu). |

展览现场照片 Installation Views:

开幕照片 opening picture展览作品 works

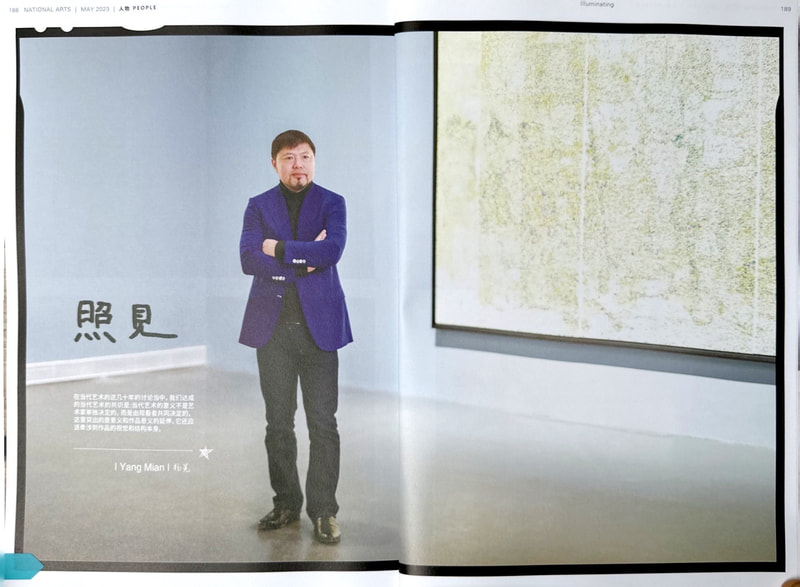

媒体报道 media reports

纸媒出版 Paper Publishing

Noblesse 2023.05

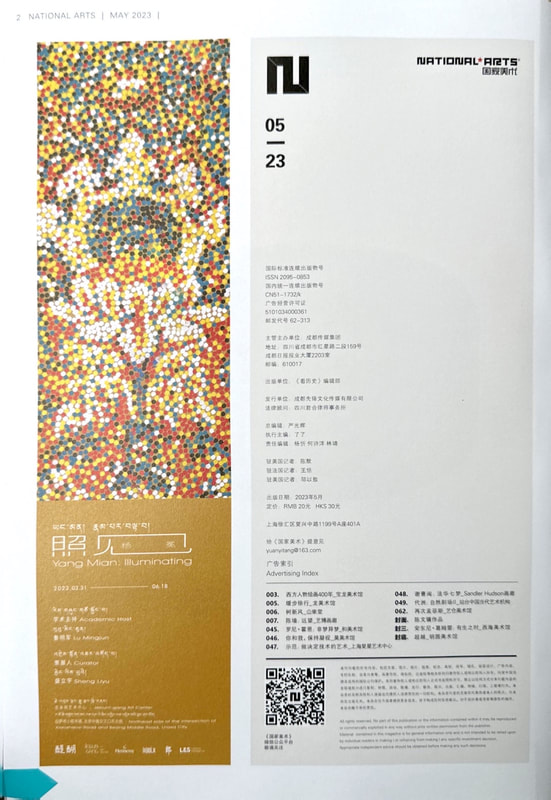

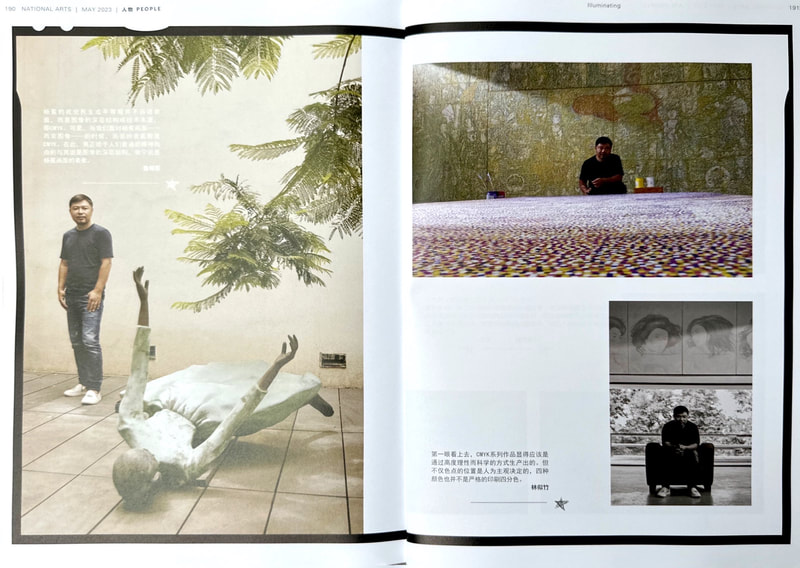

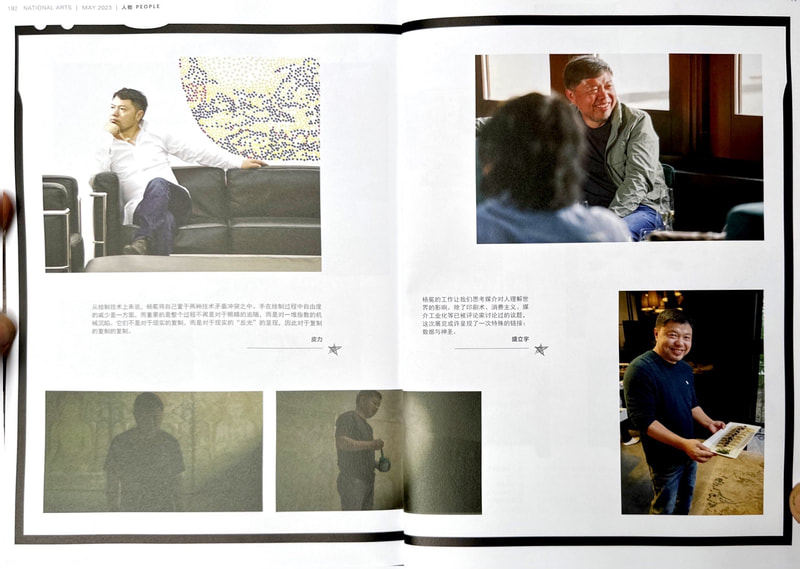

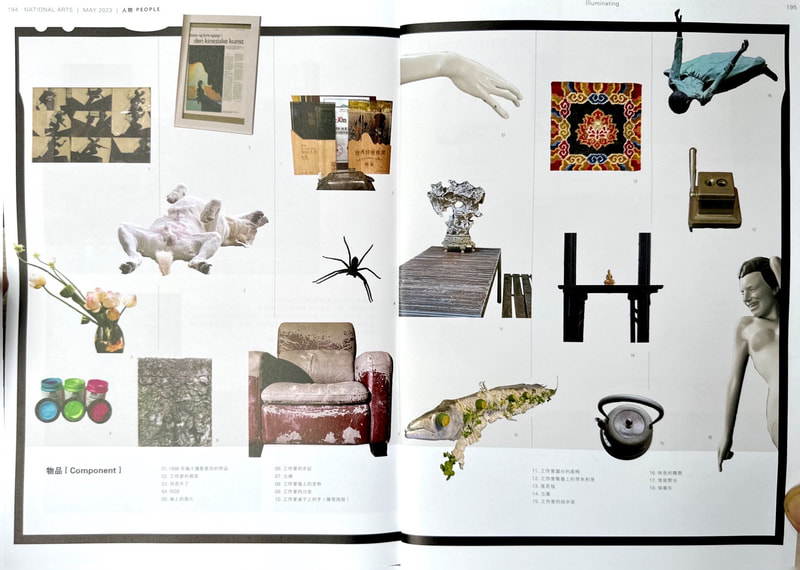

国家美术 Nationrl Arts 2023.05

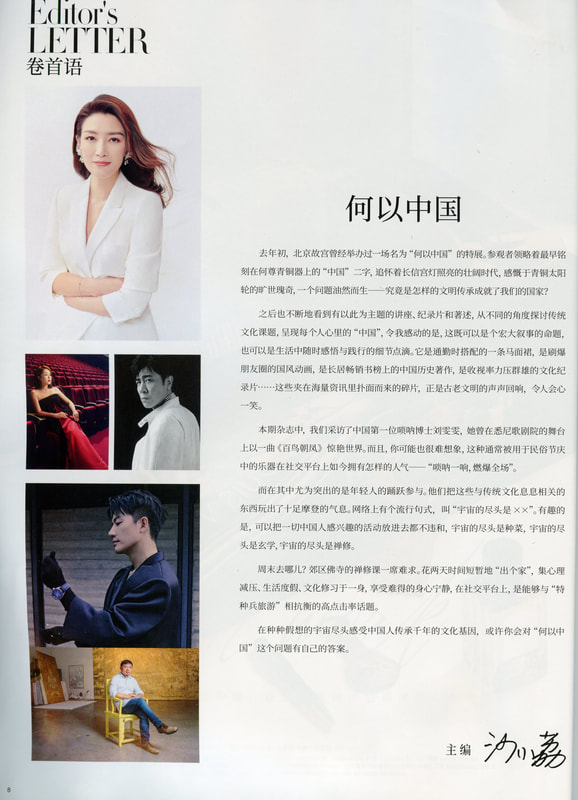

时尚芭莎 BAZAAR 2023.07

时尚甄选(敦煌的美学价值)

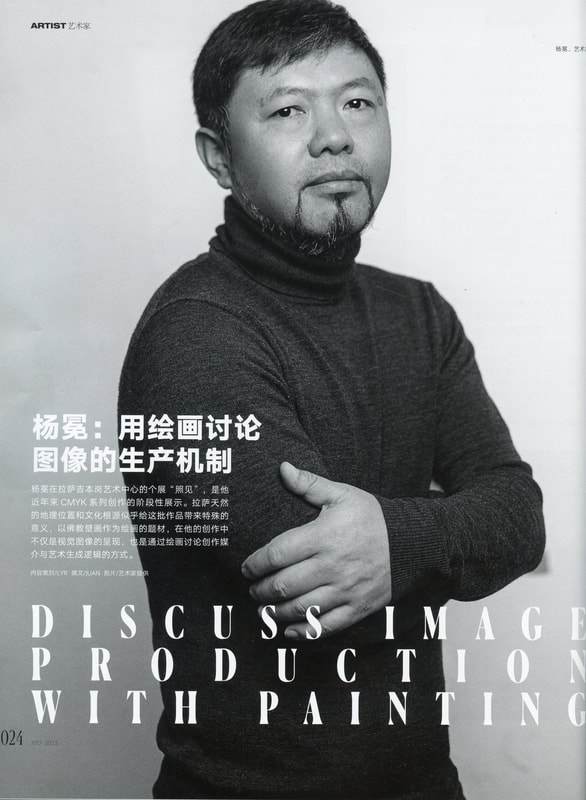

Robb Report lifestyle 2023.07 公共教育public education

|